2024.11.02 – 2024.12.23

Guillaume Dénervaud: Oxyde Ballad

“Antenna-tenna” is honored to announce the solo exhibition Oxyde Ballad by artist Guillaume Dénervaud, which opens on November 12, 2024 and will run through December 23, 2024.

–

Harry Burke is an art critic and a PhD candidate in art history at Yale University, New Haven.

An oxide is a chemical compound that consists of oxygen combined with another element. We encounter oxides all the time. Carbon dioxide—a metabolic waste product that’s essential to plant photosynthesis, and a greenhouse gas created by burning fossil fuels—is an oxide. So is carbon monoxide, which fills our lungs when we smoke. Steel becomes stainless when a microscopic layer of chromium oxide is applied to its surface. Iron oxide is commonly known as rust.

Oxyde Ballad, Guillaume Dénervaud’s first solo exhibition in Asia, explores the associations between oxides, painting, and industrial decline. Oxides feature in numerous natural and synthetic pigments, and catalyzed the emergence of the modernist avant-garde. They are also wily protagonists in many of this century’s most acute environmental issues. Through various strategies, the works on view at Antenna-tenna stage a dialogue between these concerns.

Natural iron oxides—earthy ochres, siennas, and umbers—were used by cave painters, and appear throughout medieval and early modern palettes. After many thousands of years of natural pigment use, the nineteenth-century invention of synthetic iron oxides, as well as other commercial pigments, revolutionized painting. The introduction of metal paint tubes enabled the Impressionists to wander out of their studios and paint en plein air, while synthetic pigments gave greater density and consistency to the colors they were mixing, encouraging experimentation. The teal green Viridian (PG18), a hydrated chromium oxide now recognized to be toxic, can be seen in works like Édouard Manet’s The Balcony (1868-69) and Claude Monet’s Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare (1877), to name just one of these hues.

The creation of synthetic pigments directed attention to the surface of the canvas, a move that became a cornerstone of modernist theory. If high modernist painting is praised for its reflexivity, the works in Oxyde Ballad conversely call us to look around us, at our environment. Dénervaud mills dry pigments like Iron Oxide Yellow, which contains ferric oxyhydroxide and aluminum oxide, into his walnut oil in The night of August 27th (all works 2024). This painting, which also incorporates an oil color made of fossilized monkey puzzle tree, has the aura of rust. It’s a meditation on the interrelatedness of decay and renewal, and a reminder that no surface, no material, is truly stable. It’s less of an impression than an atmosphere.

In her book Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography (2024), Siobhan Angus discusses the critical role of mined materials (for instance silver, bitumen, or rare earth minerals) in the development of photography, and unpacks the medium’s environmental imprint. The art historian examines how iron, used in cameraless cyanotypes and blueprints, is at once a key player in industrialization and an essential nutrient in human and plant growth, and positions this mineral as an “unstable boundary” between human and more-than-human realms.1 Dénervaud probes how such boundaries both endure and corrode. Lanterns Avenue—dominated by a seething, saturated orange—depicts a cluster of dots and spheres, some linked together by veins, floating, like bubbles, over latticed pipes. Like many of the artist’s works, it fuses the languages of scientific illustration and painterly abstraction, and presents a leachy assemblage of organic and inorganic forms.

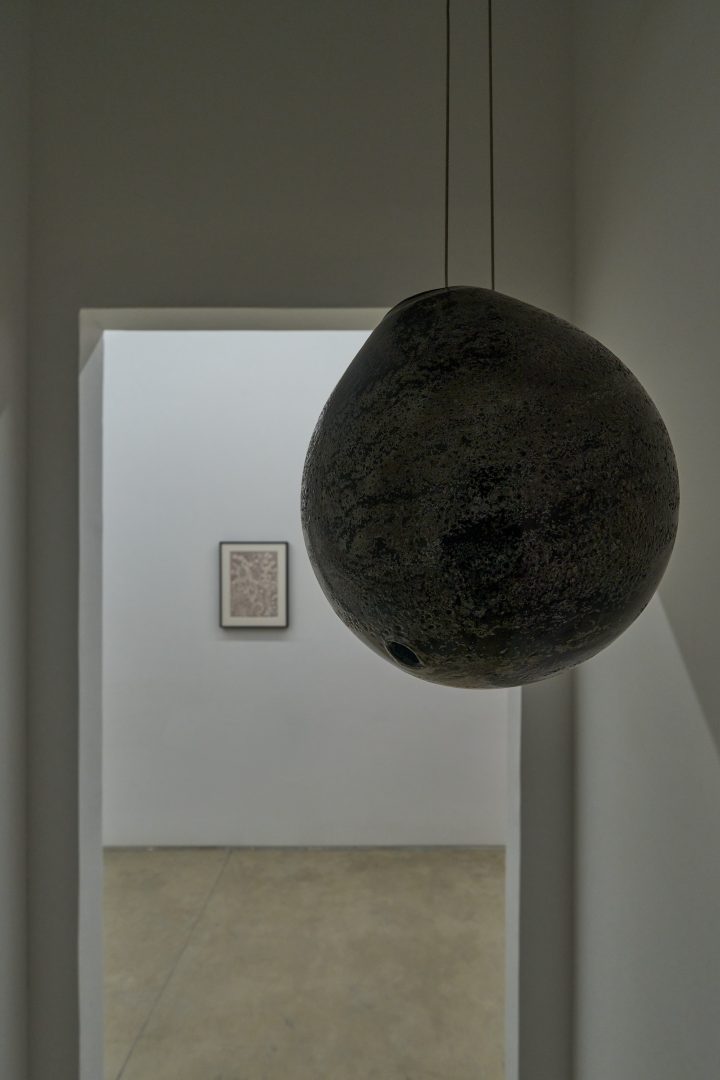

A series of ink-on-paper drawings and hanging sculptures accompany the paintings. The drawings, which bring to mind textile designer and socialist activist William Morris’s decorative prints and wallpapers, popular during the late nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts movement, portray a thriving ecosystem of plump, fibrous matter. Meanwhile, handblown glass sculptures, suspended by wires from the gallery’s ceiling, evoke the globose bodies of comets, viruses and atoms, pointing to the ambiguous scale of many of the works on view.

What do these artworks say in this time of planetary upheaval? Recent decades have seen waves of scholars consider the vitality of the more-than-human world. For instance, Jane Bennett, in Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (2010), theorizes the agency of nonhuman materials, and stresses the urgency of studying entanglements and inter-formation.2 In related work on race and disability, Mel Y. Chen analyzes how the “fragile division” between animacy and inanimateness has been wielded as a disciplining force, yet also attends to the queer, communal lifeways made possible when we redraw the borders between, say, the human and the animal, or bodies and chemicals.3 In kinship these ideas, Dénervaud asks us not only to notice the lively minerality of paint or glass, but to see from the perspective of minerals, whether this means facing up to the incomputable damage of extraction, or charting wider, wilder kinds of interbeing.

1. Siobhan Angus, Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2024), 136.

2. Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010).

3. Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 2.

–

About the Artist

Guillaume Dénervaud (b. 1987, Fribourg, Switzerland) lives and works in Paris. The artist studied at the École des arts appliqués, Geneva and at HEAD, Geneva.

Solo exhibitions of Dénervaud’s work include: Thulite, Atrata Paris (2024); Ozoned Stations, Swiss Institute, New York (2023-2024); Orphaned Wells, Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich (2024); Synthetic Splinter, Bel Ami, Los Angeles (2023); Surv’eye, Centre D’édition Contemporary (CEC), Geneva (2021); Zone Furtive, Balice Hertling, Paris (2019); Inversens Clinic, Alienze, Lausanne (2019); Spectrolia Corporation, Hard Hat, Geneva (2018).

Group exhibitions that have shown Dénervaud’s work include: Le MAMCO, de mémoire!, MAMCO, Geneva (2024); Crumbling The Antiseptic Beauty, Fondation d’Entreprise Pernod Ricard, Paris (2024); Toward the Celestial: ICA Miami’s Collection at 10 Years, ICA Miami (2024); La main-pleur, Kunsthalle Friart Fribourg, Fribourg (2022); Des corps, des écritures, Musée d’art Moderne (MAM), Paris (2022); Aquarium, Maison Populaire, Montreuil (2022); Formes du Transfet, Magasins Généraux, Paris (2021); Emblazoned World, Bel Ami, Los Angeles (2021); Le sain ennui, BQ gallery, Berlin (2021); Your Friends and Neighbors, High Art, Paris (2020).

Dénervaud has participated in residency programs at the Swiss Institute, New York (2021) and the Fondation d’Entreprise Hermès, Paris (2019). His works are part of the collections of the ICA, Miami; the MAMCO, Geneva; and the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris.

–

Antenna-Tenna

B1-7, 9 Qufu Road, Jing’an, Shanghai

Wednesday to Saturday 11:00-18:30

Installation Views

Artworks

-

Guillaume Dénervaud, Galvanized Advices, 2024

Distemper and oil on linen

160 x 110 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Lanterns Avenue, 2024

Distemper and oil on linen

160 x 110 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, The night of August 27th, 2024

Distemper and oil on linen

160 x 110 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Creepers Hill, 2024

Distemper and oil on linen

160 x 110 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Daylight Company, 2024

Distemper and oil on linen

160 x 110 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Vacuum Energy Label, 2024

Distemper and oil on linen

160 x 220 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Key Hub Unit 14, 2024

Distemper and oil on linen

160 x 110 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Ventilated Square, 2024

Distemper and oil on linen

160 x 220 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Low Heat Building, 2024

Ink on paper

36 × 26 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Eminigus Clouds, 2024

Ink on paper

36 × 26 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Transit Brokers, 2024

Ink on paper

36 × 26 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Mount Stability, 2024

Ink on paper

36 × 26 cm

作品信息Information -

Guillaume Dénervaud, Skeptical Fields, 2024

Ink on paper

36 × 26 cm

作品信息Information