2022.11.08 – 2023.02.28

Daisuke Fukunaga: Fertile Break

Antenna Space is delighted to present the first solo exhibition of Japanese artist Daisuke Fukunaga in China, Fertile Break, from November 8, 2022 to February 28, 2023.

Beginning with a Break

Words / Yuan Jing

Translate / Bridget Noetze

In Fukunaga Daisuke’s large paintings, a man reclines on a park bench, four people chat and laugh as they sprawl on a lawn, and a young woman sitting on a moped enjoys a cigarette. Of course, the gentle tones, the calm expressions, and the floating figures are relaxing for viewers, but because time feels like it’s stagnating, those same viewers start to uneasily seek out a center of gravity. In the end, the industrial facility on the far end of the lawn spewing smog, the obvious monochrome work clothing that the figures are wearing, and the almost glow-in-the-dark hardhats scattered on the ground or held in the lap point to the true protagonist of the paintings: work.

The first painting that imprinted on Fukunaga Daisuke’s mind was Jean-Francois Millet’s painting The Gleaners (Des glaneuses), which he saw on a childhood trip to a museum with his parents—this may have been his first impression of work. Moreover, he has lived in the countryside around Tokyo all his life, and the landscapes in Millet’s paintings would have seemed familiar to him. However, Fukunaga grew up during a period of rapid economic growth in Japan, and his youth was marked by the various problems that arise from work, which in turn shaped his thoughts about work and gave him conflicted feelings about it.

Millet extolls the beauty of work in a romantic way, while Fukunaga chooses to focus on the breaks between bouts of work. The postures and expressions of his figures help the viewer to envision or build an image of work—the figures enjoy relaxing after a hard day or feel heavy and powerless due to overexertion. Through painting, he resists—though very gently—the various problems surrounding work. In his early paintings, he focused on mops, tires, and other objects that often appear at workplaces. For him, “If all the world’s a stage, then I don’t want the hero to be the protagonist; instead, [I want to highlight] the objects that are waiting behind the curtain backstage, an uncertain and restless mood, and the memories and visions inspired by encounters with those scenes and objects.” As Georges Bataille once described work:

Of course, it is work that separated man from his initial animality. It is through work that the animal became human. Work was, above all else, the foundation for knowledge and reason. The making of tools and weapons was the point of departure for that early faculty of reason which humanized the animal we once were. Man, manipulating matter, figured out how to adapt it to whatever end he assigned to it. But this operation changed not only the stone, which was given the desired form by the splinters he chipped from it, but man himself changed. It is obviously work that made of him a human being, the reasonable animal we are.[1]

The objects and figures in Fukunaga’s paintings are fundamentally transformed by work, which places them on equal footing. He paints a world changed by work, a world slowly unfolding because of this pause, this break in the action.

These paintings about work are records of personal stories and memories. We could say that the figures in the paintings are all representations of the artist; their “legs and […] arms are full of torpid memories,”[2] as Proust wrote in In Search of Lost Time. In these torpid limbs, past work imbues the body with unconscious memory.

Thus, work in Fukunaga’s paintings is not presented concretely as an element in society’s production system. More often, it is part of an individual’s consciousness, dissociated from work as a social output. This dissociation actually stems from a question: Can work make us happy?

Fukunaga has painstakingly smoothed out the divisions between the figures and the background, presenting them with an almost homogenous granularity—it seems as if they are covered with a layer of dust. Before his question can be answered, people are simply confined within it. However, his soft, ambiguous tones are like the traces left after the caress of time. The hazy, quivering colors seem to come from light reflecting off of the dust, changing with each moment and telling us that this dust is where dreams grow.

This place exists because breaks (ま, pronounced “ma”) exist. Fukunaga Daisuke focuses on the breaks, these in-between moments that are critical in Japanese culture. They are the voids in paintings, but they have a broader meaning. These breaks are the distance that the artist keeps from his memories, the gap between the physical and the spiritual, and the opposition between people and objects. Because of these breaks, people can exist in a still, reflective state and something rich and fertile emerges between the inhale and the exhale.

References:

[1] Bataille, Georges. The Tears of Eros. Translated by Peter Connor. San Francisco: City Lights Publishers, 1988.

[2] Proust, Marcel. In Search of Lost Time Vol. 4: Time Regained. Translated by Andreas Mayor and Terence Kilmartin. Edited by D. J. Enright. New York: Random House, 1993.

Installation Views

Artworks

-

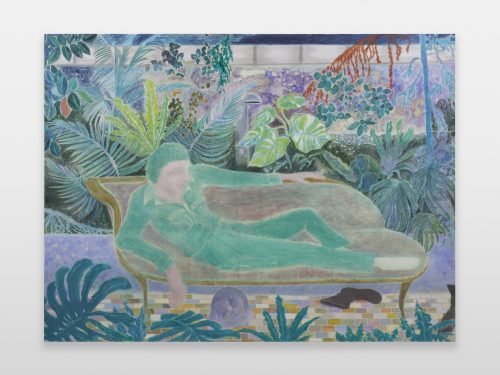

Daisuke Fukunaga, Fertile Break, 2022

Oil on canvas

194 x 259 cm作品信息Information -

Daisuke Fukunaga, A Man Drunk with the Fragrant Olive, 2022

Oil on canvas

116.7 x 72.7 cm作品信息Information -

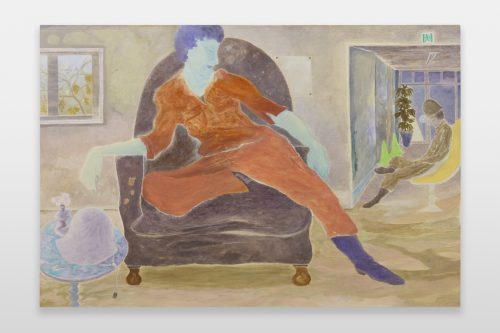

Daisuke Fukunaga, Sleeping Guys, 2022

Oil on canvas

130.3 x 194 cm作品信息Information -

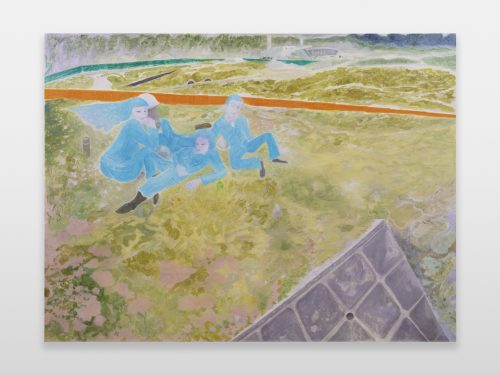

Daisuke Fukunaga, Lunch on the Grass, 2022

Oil on canvas

194 x 259 cm作品信息Information -

Daisuke Fukunaga, Intimacy Talking, 2022

Oil on canvas

65.2 x 100.0 cm作品信息Information -

Daisuke Fukunaga, Meditation, 2022

Oil on canvas

65.2 x 65.2 cm作品信息Information -

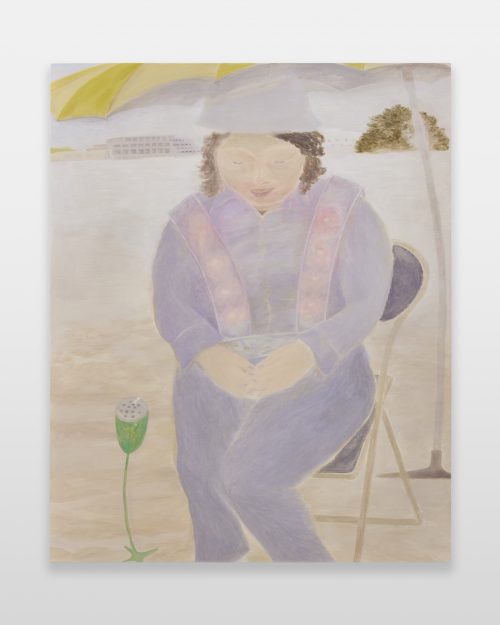

Daisuke Fukunaga, Under the parasol, 2022

Oil on canvas

162.0 x 130.3 cm作品信息Information -

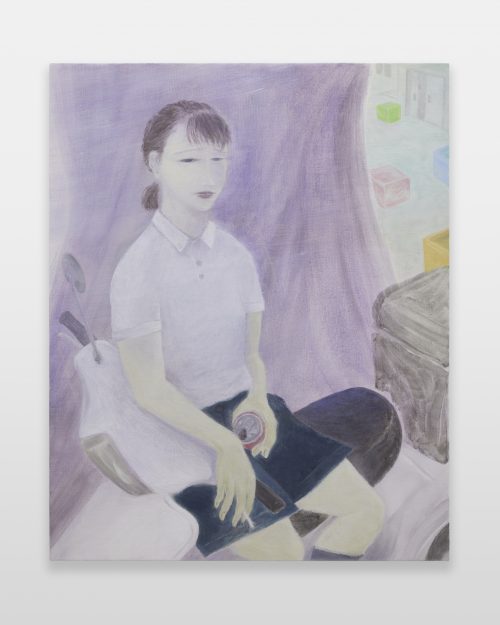

Daisuke Fukunaga, Smoking Time, 2022

Oil on canvas

100.0 x 80.3 cm作品信息Information