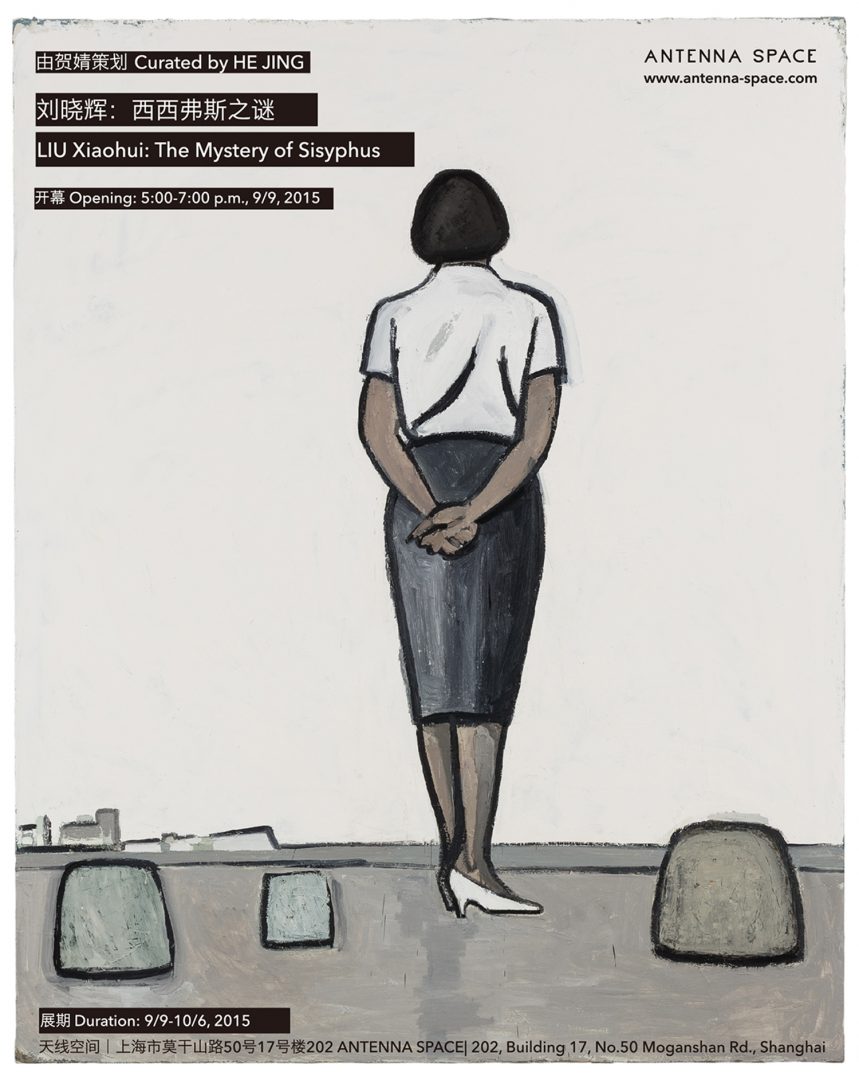

2015.09.09 – 2015.10.06

Liu Xiaohui: The Mystery of Sisyphus

Text: He Jing

Translation: Hanlu Zhang

How far is the distance lying between a series of painting and an exhibition of that series of painting? This is the question stuck in my mind ever since my first visit to Liu Xiaohui’s studio. For an artist who has devoted himself in the studio thus rarely exhibited, what matters is this: in order to move the works from the studio to the gallery and make sense, the exhibition is regarded as something urging the transformation of viewing experience from the private to the public. Here, “why exhibit” and “how to exhibit” become one question, and the solving of the latter shall bring us the answer of the former. Exhibition as a mechanism has to provide a more concrete and clarifying vehicle for the aleatory vision in the studio. Therefore, if we resolve the question “how to exhibit”, the answer to the more ontological question of why should we move the viewing from the studio to the gallery emerges. Liu’s painting, strangely, with its monotonous repetition, offers extended possibilities of imagination. When the exhibited works are somehow visually unified, it is more likely that we treat the methodology behind such unification as the starting point of the exhibition. In other words, the symptomatic repetition on Liu’s canvas induces our investigation into his methodological meaning, which, both for the artist and for the viewer, seems more reliable, or more real – according to Liu himself.

Why does the silhouette of the same woman appear in Liu Xiaohui’s oeuvre again and again? According to the artist, “she” comes from a scene in Yasujiro Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon where we see a female who turns around and leaves after delivering some food. Liu admits that his capture of this image may just be “unconscious”, but he regards her mysterious and charming. As a matter of fact, before delving into the psychoanalysis of this visual appropriation, we might need to distrust the artist’s remark. Tireless repeating certain image can be understood as being spiritually attached it, but in his work, Liu paints over, modifies, and betrays the original image – “she” is not “she” anymore. She starts in Ozu’s lens, but she varies in Liu’s work: she walks, she stands, she is faced with the ocean, and she gazes at the land afar. The repeated silhouette, in its silent variation, becomes an archetype of Liu’s visual system. Meanwhile, Liu does not extend the image to a sort of vertical script, but rather, he keeps it at where it starts. Also, the silhouette varies in a radiant manner, but its framework remains what it is the point when the filmic moment enters Liu’s canvas. In other words, the “she” in Liu’s constructed visual world never gets a chance to keep living; instead, she is a borrowed image, flat and empty inside. That is because the artist takes the silhouette as departure and intends for something else. Liu appropriates the image and takes it as agency, through which a much difficult situation is revealed. For Liu, it is an experience of perennially approaching but never reaching “truth”, an obsession, a Sisyphean process. In that sense, the monotonous repetition of one image reinforces the unrepeatable acts and methods of painting behind it. It alludes to something more metaphysical than the image itself. Sisyphus has become a hero in Greek Mythologies because his endless act of rolling up the boulder symbolizes grief, not desperation. In his battle with the mountain, the process is much closer to truth, if there is any, than the result. Therefore, Albert Camus in his essay Le Mythe de Sisyphe pictures a “Happy Sisyphus” who, rather than being desperate in a fruitless narrative, is satisfied during the process of eternal repetition.

That said, Liu Xiaohui is more interested in the process of repeatedly painting than the repetitive image itself. Or, we can say that he starts all over again and again just to subvert those “finished” images. The homogenization of the visual product is only fantasy, in some sense, or camouflage. Painting over and even covering the same picture is the real game. In addition, the artist acknowledges “labor” in creative process. In fact, for Liu, painting is never supposed to be “creative”, but a laborious daily routine. It is important because what it brings is a quantitive accumulation in which the artist commutes between affirmation and negation. Liu regards quantity more “reliable” and “reasonable” than any exterior impact during the painterly process. There is a paradox. Liu’s work turns out to be more about reduction than addition in that the more the physical movement or color layer are applied, the less there is anything left, because repetition eventually leads to erasing, cleansing. Liu negates the kind of symptoms and traces that are decorative, pretentious, and superfluous, which may come from years of academy training or some “correct” current visual models. He erases them again and again. According to the artist himself, “the work does not leave any extra possibilities; it will become less and less, eventually a flat iron.” Here, “less” does not mean anything quantitive, but something closer to “an experience” proposed by John Dewey in his Art as Experience. It is an experience as a whole, in which “every successive part flows freely, without seam and without unfilled blanks, into what ensues.”[1] It is tightly interwoven in an organizational sense and it prevents any exterior possibilities from invading or intervening. This is a difficult process, requiring the artist’s alert and high self-consciousness. He has to make precise and consistent decisions about the image during the endless erasing and covering. What makes all even more difficult is that the “process” is not measured daily, but rather, Liu spends weeks or even months finishing one painting. One image may takes up a period of time, and during that period of time, the artist may be working on multiple images simultaneously. Here, the experiential consistence weighs larger than timely coherence. What matters is the connection and fluctuation on the conscious level. For Liu, “truth” or “clarification” come from subjective experience and judgement. That is why it is important to inquire the process and methodology behind Liu’s canvas. The consciousness to keep the experiential and judgmental consistence is itself aesthetic. The meaning emerges before the image is finished; or, we can say: the meaning has led the eventual appearance of the image. Started from the woman in Ozu’s movie, what Liu wishes to produce is not another image, but a metaphysical image. His work attempts to enclose the figurative images inside the painting through repetitive modification and erasure. The entire process is done in high self-consciousness. Just as Camus puts it, “the reason why the myth of Sisyphus is a tragedy is because he is conscious (about his action).”[2] “Tragedy” here is not only in an emotional sense, but also philosophical; it refers to metaphysical truth.

However, for the viewer or for Liu himself, when we try to reflect on the visual form according to the creative process, we would still find it hard to make out of things. As mentioned above, take the outer layers of the image as border, we are actually excluded by the inner ones. Therefore, from the behavioral to visual level, these repetitive images become obscure, or even mystified. Such mystification is related to the detailed decisions made during the process: compared to those who considerate everything before painting, how to start and how to start etcetera, Liu belongs to the type of painters who vacillate only towards the end. Edvard Munch is among the latter type too and he often says: “I stop only when I can’t possibly work anymore.”[3] Here, “possibly” certainly refers to subjective decisions. Sometimes, Liu puts aside a “finished” work and reworks on it after a while. That painting may have already been painted over several times, the image covered and recreated. He keeps subverting his own decisions as if a destination becomes impossible. In terms of why this painting is “done” and other not done, why the repeated painting-over, we may never know. Liu thinks that “nothing is that reliable,” as he would always negate his own possibility. For him, the repeated negation seems more positive than possibilities. If we look further, we will find that the repetition is only in the behavioral sense, and every starting-over-again is supported by very detailed reasons: maybe a color patch or maybe a line is not “reliable”… These reasons cannot be more convincing because they are too subjective and detailed for the viewers to be part of it. It is like a proposition whose method and logic are clear, but the deduction and the result remain obscure.

This is the paradox. This is not only the paradox in Liu Xiaohui’s work, but also between his painting process and its result image. If this exhibition attempts to pave a way for the viewers to understand Liu’s visual system through emphasizing his repetitive process, then, when we further ask how does the repetition heterogeneously evolve, our recognition and judgment are blurred. And when our vision eventually gives up the burden of thinking and inquiring and lays on the canvas, it is met with frustration, unknownness, and mystification. This is a road which leads forward but on which we have to step backwards to get there. When the audience steps “back” in front of Liu’s paintings, some mysterious “lumps” emerge. These lumps then become solidified and frozen, hanging between strokes, color, and lines, preventing them from interacting with each other and integrate into one complete, gentle image; what they bring are stagnation and weight. Mysterious black lines repeatedly touch and leave the repeated image of the woman, with coarse accuracy and hasty calmness. After all, these lumps form in the picture certain spiritual barrier and high density cased by perennial laborious experience. As Camus describes it, the most touching moment in Sisyphus’s life is that paused moment when each time after the boulder is finally rolled up to the mountain top and about to fall down again. In Liu Xiaohui’s work, those mysterious lumps are both physical and spiritual. They head towards the end of the image through a painting process that repeats itself again and again. They put objects’ realness into question and call for the uncertainty of perception, and meanwhile, they explore spirituality under layers of practical experience. If the realness of “truth” is actually contained in that mysterious silhouette, the real myth of Sisyphus is then the unreachable, the moving back and forth between negativity and positivity, the body of Sisyphus that embraces absurdity, as well as the shadow he casts into reality.

————————————————————

[1]John Dewey, “Art as Experience”, The Later Works of John Dewey, 1925-1953. Volume 10: 1934, edited by Jo Ann Boydston Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1987. P 43.

[2] Albert Camus, Le Mythe de Sisyphe, Essai sur l’Absurde, Éditions Gallimard, 1942. P 165.

[3] See Exhibition Edvard Munch: L’œil Moderne 1900-1944 at Centre Pompidou, 2012. (Online resource:http://mediation.centrepompidou.fr/education/ressources/ENS-Munch/ENS-Munch.html#) “[…] Je me suis finalement arrêté quand il n’était simplement plus possible d’y travailler.” from Edvard Munch, Projet de lettre à Axel Romdahl, N3359, 1933, Oslo, Munch-museet. Translated from Norwegian by Luce Hinsch.

Installation Views

Artworks

-

,2015s-500x210.jpg)

Untitled – Seaside

Oil on canvas

3 panels, 250 x 200 cm each

2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Green Ground

Oil on canvas

250 x 200 cm

2014-2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Corridor No.1

Oil on canvas

220 x 200 cm

2014-2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Corridor No.2

Oil on canvas

180 x 160 cm

2014-2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Green Skirt

Oil on canvas

180 x 160 cm

2014-2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Sitting Position at Seaside No.1

Oil on canvas

160 x 150 cm

2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Sitting Position at Seaside No.3

Oil on canvas

160 x 150 cm

2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Sitting Position at Seaside No.4

作品信息Information -

Untitled – Blue Dress

Oil on canvas

73 x 50 cm

2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – White Dress

Oil on canvas

73 x 50 cm

2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Green Skirt Standing Position

Oil on canvas

33.5 x 24.5 cm

2014-2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Green Skirt Sitting Position

Oil on canvas

33.5 x 24.5 cm

2014-2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – Grey Skirt Sitting Position

Oil on canvas

30 x 40 cm

2014-2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – White Dress No.1

Oil on canvas

33.5 x 24.5 cm

2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – White Dress No.2

Oil on canvas

33.5 x 24.5 cm

2015作品信息Information -

Untitled – White Dress No.3

Oil on canvas

38 x 46 cm

2015作品信息Information -

,2015s-1-500x210.jpg)

Untitled – Seaside

Oil on canvas

3 panels, 40 x 30 cm each

2015作品信息Information