2015.07.28 – 2015.09.02

Curator: Liu Ding

Southern Wind: Nadim Abbas, Wang Shang, Gong Jian, Li Ran, Hao Jingban, Adrian Wong, Song Jiayi

LIU Ding

In 2013, I visited the grave of Karl Marx in the Highgate Cemetery of Northern London; on my way there, the encounter I had with some fellow Chinese proved to me once again that perhaps Marxism had never really been to China at all. It was just a series of vocabulary and expressions borrowed, and hijacked, by another kind of political ideology. Today people from China are still traveling around and shopping in London in the name of Marxism; they would also carry out the ritual of paying tribute to Karl Marx by visiting Marx’s grave, holding oath-taking ceremonies, and leaving flowers at the grave. Actually I believe that those Communist Party members I met and followed all the way to the Highgate Cemetery, who got angry and threatened me to delete the contents in my cellphone when they found out that I was taking pictures of them, did not really have any sense of empathy with the portrait of the old man right in front of them. Marxism, as a foreign language and system of thoughts, has never been adopted properly or treated as China’s own child. It has always been just a name.

In the summer of 2015, I spent an afternoon at the Mauerpark in Berlin, visiting remains of the Berlin Wall with my family. My child was playing in a small playground, which was surrounded by railings and equipped with a sandpit. There stood a giant slide installation made of colored wood strips that allows the kids to climb up and down. Looking from the playground, hippie-looking men and women were having barbecue on an extensive spread of land full of overgrown grass and weeds, with drunken homeless here and there, stray dogs wandering around and pieces of beer bottles everywhere on the roadsides. Some older men were playing shot put. An old dog in the basketball court was hit and kicked by those young players now and then, but it remained unmoved. After seeing us, the dog walked forward in wobbly steps, but had no strength even to wag its tail. Graffiti spread on every inch of the wall, along which many shabby swings, occupied by both children and adults, evenly installed alongside the wall. Three dancer-looking youngsters in ragged shirts were practicing handstands, climbing, and single-leg-standing on stakes in a sandpit of the playground. They laughed and talked among the kids, as if there were nothing to be concerned about in this world. It was such a slice of reality evocative of the flavour of a utopian world at the footing of the Berlin Wall at that moment. It got me wonder, under the current circumstances of globalization, what social structures and ways of organizations could have generated such a scenario.

An artist friend, who had moved to Berlin from New York, told me that she would rather live the life with no production and no pressure in Berlin, than going back to New York. Another artist friend, moved to Berlin from Stockholm many years ago, said that only in here existed a broader world, with possibilities and horizons. Nurseries, kindergartens, and playgrounds could be seen in every block; young parents told me it’s easy to raise kids here. Can I believe all of these? Is THIS the city of Utopia? For me, I was just a tourist of the city, I knew nothing about it. However, all this information made me think, not about how hard it had been to live and work in China, especially in large cities like Beijing and Shanghai; but about how pale, limited and unreliable terminologies are, which we had become so accustomed to, when being used by us to describe and understand the complexity of real situations. We are familiar with words such as “Socialism system” and “Capitalism society” which can hardly come close to fully express the multiplicity of the reality. In this sense, any claim of loyalty and correctness concerning either side of political systems are just cognition and attitudes based on one-sided experience. On one hand, the reality is constantly changing; on the other hand, words are subject to reinterpretation, translation and projection through the lens of ideologies in the process of being communicated and disseminated. They are words deviated from their original meanings, and are foregrounds with different intentions within different situations. Maybe it’s time for us to talk about how the words, as foregrounds, have been displaced from their original meanings? And to think about if we could still depend on them as co-ordinates to map out our path and behavioral patterns? In modern China, we are used to a large number of words and concepts, and are concerned about their “recognition” or “being recognized”, their “reversal” or struggling for “displacement”; such is still taking place today. Let us now put these “struggles” aside into the files for the moment, and take a look at those absolute signals we sent out in the near past.

Since Deng Xiaoping’s Southern-Tour-Speech in 1992, “South Wind” has become an expression charged with political connotation other than just being a pure noun describing natural phenomenon as how it came into being originally. It has been mentioned, superimposed, distributed, and repeated in political discourses ceaselessly. It slowly occupied people’s experience, and became internalized as a political concept in a very swift period, and eventually became a part of the universal value. In this sense, “South Wind” is not south wind anymore, it has nothing to do with wind direction. As a concept attributed to the geo-political category, the spread of “South Wind” reminds us that the process of the formation of ideology is a political will working itself from top down. It gradually evolved into a kind of collective consciousness through being wide spread, and it could even become a seemingly self-evident “code-word” and a prescribed expression, while actually most people could not articulate its political connotations accurately.

In this accustomed experience and perception, “South Wind” is a word full of resonance of the 1990s, a poetic abstract noun with imagery of openness, hope, free spirit, and freshness; while it is underlied by the country’s wave of irresistible reform. The wave successfully concealed politics into the logic and discourse of economic developments after 1989, and it subtly made everyone, including intellectuals and artists, involved into a hope towards democracy embedded in economic developments, which even started to become a kind of conviction of an almost religious status. Economic developments were gradually dealt with and considered by most as the ultimate content and target, and guidelines for behaviors and values, but not as a process and strategy towards realizing a democratic horizon.

Such a neutralized term as “South Wind” makes the political intentions behind the coining of such terms less visible, and it becomes the synonym of a “liberal” and “open” spirit. In essence, it was such a powerful political strategy to identify, to rationalize those identified imageries, and to make them the basis of values. We can’t deny that today all of us are moving around according to a map which is made up by various types of political strategies and intentions. The paths and directions that we could see with our eyes in front of us are actually also obstacles and barriers in our adventurous exploration.

Same things happened in the contemporary art field in China after 2010: artistic capital, together with nationalism, swept through the art industry like a hurricane, which was exactly a kind of “South Wind” for art, and became something of a directory map as well. Artists no longer have patience for humble and respectful dialogues with other fellow artists in other parts of the world; their works are wandering around in various exhibitions like empty shells. Artists, collectors, museums, curators, auction houses, and gallerists obtain their pleasure and confirmations in trading business again and again. And those artistic shells gradually integrated themselves into this hurricane.

I believe that “South Wind”, as an exhibition title, is a valuable one. Thus I would take the risk to organize such an exhibition in which the contents of the artworks are not always directly related to its title. Here I would like to thank Simon Wang, the participating artists, and the Antenna Space for their trust and commitment towards taking such an adventure together. The works exhibited are generally irrelevant to the thinking of “South Wind” in a direct or immediately obvious fashion. This is an exhibition that is shaped by free expressions of the artists plus multiple wills and intentions of different individual parties involved. I am not sure whether I could truly grasp and make apparent in the show the inherent intentions of all the exhibited works, neither could I fully recognize the innermost thoughts of each participating artist. However, an exhibition is an invisible shell, an action worth the risk, and a bond that connects us; so we could stay together waiting for the disappearance of absolute signals in the midst of today’s hurricane.

Translated by GU Qianfan

Installation Views

Artworks

-

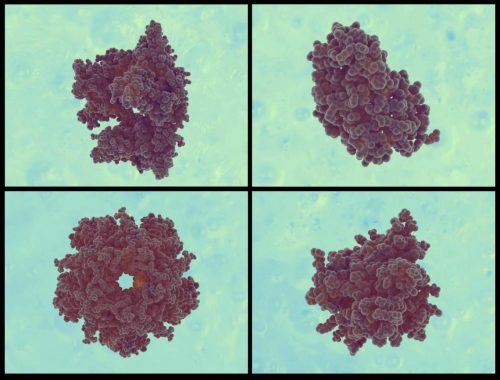

Nadim Abbas, HBV/HIV/HPV/HSV, 2013

Video Installation

6 mins 24 secs (each)

Exhibition Size: 300 × 400 cm作品信息Information -

-500x750.jpg)

Wang Shang, Crying Head, 2014

Sculpture

60.5 x 60.5 x 178 cm作品信息Information -

Wang Shang, Pieris Rapae, 2015

Acrylic on Canvas

150 x 150 cm作品信息Information -

Wang Shang, Marpesia Iole, 2015

Acrylic on Canvas

130 x 165 cm作品信息Information -

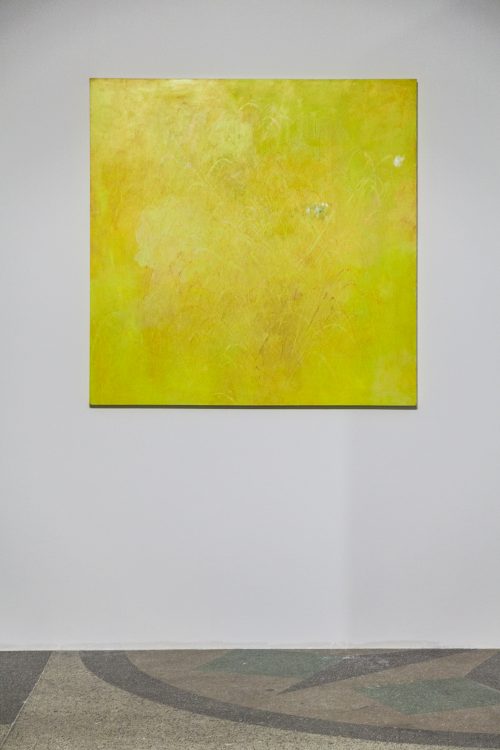

Gong Jian, Swan No. 4, 2015

Acrylic on canvas

220 × 165 cm作品信息Information -

Gong Jian, Swan No.5, 2015

Acrylic on canvas

220 x 165 cm作品信息Information -

Adrain Wong, Dream Cosmography, 2015

Video Installation

7 mins 30 secs作品信息Information -

Adrian Wong, Hypnagogia IV:(Pet Supply, Sausages, Massage), 2014

Installation: 110 × 125 × 269 cm

作品信息Information -

Song Jiayi, Venerated Object – 2, 2013

Oil on canvas

230 x 110 cm (23 pieces)作品信息Information -

Li Ran, Under the Rain-Sounded Effect, 2015

Single Channel HD Video, Color & Sound

9 mins作品信息Information -

Jia Chun, Interlayper – Model, 2015

Installation

60 × 45 × 133.5 cm作品信息Information -

Jia Chun, Interlayer – Artist Book, 2015

Texts

17P作品信息Information -

Hao Jingban, I Can’t Dance, 2015

Four Channel Video Installation, HD, Colour/Black&White, Sound

34 mins 03 secs作品信息Information